Terry Holdbrooks Jr.,

29, wears the beard of a bald Amish guy, the tattoos of a punk kid, and

the twitchy alertness of a military policeman. Take him to a

restaurant, and he’ll choose the chair with its back against the wall.

Take his photo, and he'll prefer to look away from the camera.

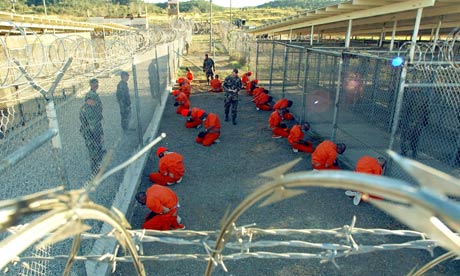

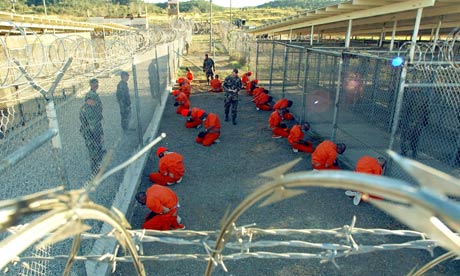

Part of that wariness Holdbrooks learned while guarding detainees from 2003 to 2004 at Guantanamo Bay, the U.S. holding tank for military prisoners on the southeastern point of Cuba.

And part of that wariness he developed after he converted to Islam while stationed at Guantanamo after months of midnight conversations with the Muslim detainees – a conversion that prompted several of his fellow soldiers to try several times to talk some “sense” into him so he wouldn’t “go over to the enemy,” as they put it.

Holdbrooks told the story of his conversion and of his observations of the controversial detention center to an audience of about 80 people at the Huntsville Islamic Center in Huntsville Saturday night, May 25, 2013. The camp, he said, tramples on every human right the U.S. has said it is against. The current hunger strike by 102 of the 166 prisoners has crossed 100 days. Many of those men were cleared to go home five or six years ago, Holdbrooks said. Their home countries tell their lawyers the U.S. won’t release them, and the U.S. tells them their home countries won’t receive them.

“They’ve lost hope. They've decided it’s better to die,” Holdbrooks said. “One of them is down to 70 pounds.”

Holdbrooks is traveling with Khalil Meek, a co-founder and executive director of the Texas-based Muslim Legal Fund of America. They are raising money for that non-profit civil rights organization, which helps pay for legal help for Muslims who are American citizens and who have been accused of vague crimes or placed on no-fly lists and other restrictions under the increasingly broad “anti-terrorism” provisions.

Even more than raising money for legal defense, Holdbrooks said, he wants to stir Americans to action. Holdbrooks’ self-published account of his experience at Guantanamo, Traitor?, was published this month -- a 164-page single-space account whittled by an editor he worked with from his 500-page manuscript. (It’s available for sale online at www.GtmoBook.com.)

“I tell this story and I wrote the book so idiot-simple that anyone could read and understand that the existence of Guantanamo is something to be ashamed of,” Holdbrooks said. “I just want to share information with people in depth and then let them make up their mind.”

“I may have become a Muslim, but I am not a traitor.”

“I may have become a Muslim, but I am not a traitor.”

12-year-old ‘terrorist’

At Guantanamo, Holdbrooks mulled over the information Army instructors has taught about Islam as he’d watched the so-called terrorists day after day. What he’d been told wasn’t lining up with what he observed. The detainees read their Qurans. They kept the daily schedule of prayers. They remained undiscouraged under horrendous pressure.

One of his duties was to escort prisoners to interrogations and then return them to their cells. He knew the kind of stresses and tortures they were undergoing in repeated questionings. He had dodged their thrown poop when anger ripped down the row of mesh wire cages. When detainees were punished with the “frequent flier program,” he’d moved men from one cell to another every two hours, round the clock.

“How can you wake up in Guantanamo and smile?” Holdbrooks asked them. “How can you believe there’s a God who cares about you?”

“I am happy to have spent time in Guantanamo,” said one detainee, the man who became his mentor, after his release. “Allah was testing my ‘deen’ (faith). When else would have I have five years away from all responsibilities, when the only thing I had was my Quran, and I could read it and learn Arabic and mental discipline?”

“Fortunately for us,” Holdbrooks said. “Most of them are bigger men than some of us would be.”

As Holdbrooks got to know the detainees, as he learned their stories during his long night shifts, he came to see the detainees as individuals. Many were men who enjoyed talking about the same things he does: Ethics, philosophy, history, religion. Many let him know what they thought of the 9/11 attacks: That they violate the teachings of Islam.

“Here, I had all the freedom in the world, and I’m miserable,” Holdbrooks said. “They have nothing, and they’re happy – it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out something’s going on.”

Tough kid

Terry Holdbrooks Jr. grew up a troubled kid with junkie parents who dumped him at 7 on his ex-hippy grandparents to be raised. By 18, he’d finished both high school – a year early – and trade school. He loved drugs, sex, rock-and-roll and tattoos – his ink would eventually cover his arms from shoulder to wrist. His earlobes have been stretched to a plug that a thumb could pass through.

So when Holdbrooks walked into an Army recruiter’s office in Arizona a year after 9/11 saying he wanted to join the Army, go kill people and get paid for it, the recruiter looked up briefly and turned back to his computer. “No, thank you,” the recruiter said.

“This was still right after 9/11,” Holdbrooks said. “The Army was flush with recruits, and they could take the cream of the crop.”

It wasn’t until his fourth visit to the office -- when he took the ASFAB, the military’s aptitude test -- that the recruiter realized Holdbrooks was worth pursuing.

Holdbrooks

signed up for military police because it offered a bonus. When his unit

was transferred to Guantanamo, the sergeant detoured through New York

to take them to Ground Zero.

Holdbrooks

signed up for military police because it offered a bonus. When his unit

was transferred to Guantanamo, the sergeant detoured through New York

to take them to Ground Zero.

“Remember what Muslims did to us,” the sergeant told the soldiers. “Remember who you’re protecting.”

So Holdbrooks arrived at the hot, seared base expecting hulking killers in every cell. What he found were doctors, taxi drivers, professors. One scary “terrorist” was 12. Another was in his 70s and dying of tuberculosis. Holdbrooks identifies himself as antagonistic, questioning, independent person. He is naturally suspicious – and found his suspicions turning in a surprising direction.

“You start thinking, ‘Was I lied to?’” Holdbrooks said.

Priceless gift

In the time he had off from his escort and cleaning duties at the prison, Holdbrooks began reading more about Islam online. The prisoner he talked the most to, a former chef from England, gave him his own copy of the Quran.

“You’ve got to realize the significance of that,” Holdbrooks said, his tough bravado breaking for a moment. “He’s in this cage for 23 and a-half hours every day. If you lose your Quran, you’re out of luck. That’s it. You’ve lost everything.”

It took Holdbrooks three nights to read it. As a restless seeker in his teens, he had studied Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism, and never saw much sense in them. In the Quran, for the first time, he found a religious text that meets his logical criteria.

“It made sense from beginning to end,” Holdbrooks said. “It doesn’t contradict itself. There’s no magic. It’s just a simple instruction manual for living.”

After three months of intense study and conversation, one night Holdbrooks told the detainee that he wanted to become Muslim.

“No,” the man said.

“Whoa,” Holdbrooks said, stirring laughter during his talk in Huntsville. “The guard wants to embrace Islam, and the bad guy says ‘no’? I must really suck.”

The detainee explained what he meant. Converting to Islam meant Holdbrooks would have to change his life. Change his diet. Quit drugs. Quit drinking. Stop profanity. Quit getting tattoos. And be prepared for his relationships to everything – wife, Army, government – to change.

Little by little, Holdbrooks made the changes. Holdbrooks found a measure of health, discipline and peace of mind he’d never had before. And he found a family.

“Every little step I took toward Islam, Islam was taking more steps toward me,” Holdbrooks said.

One night in December 2003, he was ready to stumble through the declaration of faith in Arabic. He read from a card on which the detainee had transliterated into English syllables the Arabic words for, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God.”

“I knew I’d finally said it right when their faces lit up,” Holdbrooks said.

After Gitmo

But after Gitmo, when he rotated back to the States, he lost his grip on both peace and discipline.

■ Holdbrooks addresses an audience in the fellowship hall of the Huntsville Islamic Center in Huntsville, Alabama, May 25, 2013

■ Holdbrooks addresses an audience in the fellowship hall of the Huntsville Islamic Center in Huntsville, Alabama, May 25, 2013

He was honorably discharged early -- for “generalized personality disorder,” the Army told him, although Holdbrooks wonders if his new faith influenced the decision. He and his wife divorced. He began trying to drink away his memories of Guantanamo.

“But you can’t drink away things like that,” Holdbrooks said.

By the end of 2008, he found himself wondering, “When was I happy?” The answer, he realized, surprised him: When he was in Guantanamo – because there he was being a good Muslim.

Holdbrooks been clean since 2009 – a victory he credits to following Muslim dietary codes, including daytime fasting several days a week all year, not just during Ramadan. Last fall, he married a nurse he met at his mosque. They had spent a year of careful getting acquainted in accordance with Muslim guidelines – which meant a lot of chaperoned visits. He’s finished a bachelor’s degree in sociology. He spends most weekends traveling with the Muslim Legal Fund of America to tell his story and to encourage Muslims to become involved in pushing for policy changes.

Holdbrooks is part of a small, but growing, number of former Gitmo guards who are speaking out about conditions at the center. But in addition for adding to the chorus calling for the camp’s closure, he has a message for fellow Muslims.

If the Prophet Muhammad were to come back to Earth today, Holdbrooks said, he would find the best examples of Islam in the United States. American Muslims have a responsibility to live their faith so others can see a true example, not the perversions of the terrorists or the tyranny of corrupt governments.

“You can’t be afraid to be a Muslim in public,” Holdbrooks said. “Tell your neighbors you’re Muslim. Invite them into your home. Invite them to visit the masjid to see our secret bomb factories.”

“If it’s time to pray – pray. The whole world is an acceptable place to pray.”

Part of that wariness Holdbrooks learned while guarding detainees from 2003 to 2004 at Guantanamo Bay, the U.S. holding tank for military prisoners on the southeastern point of Cuba.

And part of that wariness he developed after he converted to Islam while stationed at Guantanamo after months of midnight conversations with the Muslim detainees – a conversion that prompted several of his fellow soldiers to try several times to talk some “sense” into him so he wouldn’t “go over to the enemy,” as they put it.

Holdbrooks told the story of his conversion and of his observations of the controversial detention center to an audience of about 80 people at the Huntsville Islamic Center in Huntsville Saturday night, May 25, 2013. The camp, he said, tramples on every human right the U.S. has said it is against. The current hunger strike by 102 of the 166 prisoners has crossed 100 days. Many of those men were cleared to go home five or six years ago, Holdbrooks said. Their home countries tell their lawyers the U.S. won’t release them, and the U.S. tells them their home countries won’t receive them.

“They’ve lost hope. They've decided it’s better to die,” Holdbrooks said. “One of them is down to 70 pounds.”

Holdbrooks is traveling with Khalil Meek, a co-founder and executive director of the Texas-based Muslim Legal Fund of America. They are raising money for that non-profit civil rights organization, which helps pay for legal help for Muslims who are American citizens and who have been accused of vague crimes or placed on no-fly lists and other restrictions under the increasingly broad “anti-terrorism” provisions.

Even more than raising money for legal defense, Holdbrooks said, he wants to stir Americans to action. Holdbrooks’ self-published account of his experience at Guantanamo, Traitor?, was published this month -- a 164-page single-space account whittled by an editor he worked with from his 500-page manuscript. (It’s available for sale online at www.GtmoBook.com.)

“I tell this story and I wrote the book so idiot-simple that anyone could read and understand that the existence of Guantanamo is something to be ashamed of,” Holdbrooks said. “I just want to share information with people in depth and then let them make up their mind.”

“I may have become a Muslim, but I am not a traitor.”

“I may have become a Muslim, but I am not a traitor.”12-year-old ‘terrorist’

At Guantanamo, Holdbrooks mulled over the information Army instructors has taught about Islam as he’d watched the so-called terrorists day after day. What he’d been told wasn’t lining up with what he observed. The detainees read their Qurans. They kept the daily schedule of prayers. They remained undiscouraged under horrendous pressure.

One of his duties was to escort prisoners to interrogations and then return them to their cells. He knew the kind of stresses and tortures they were undergoing in repeated questionings. He had dodged their thrown poop when anger ripped down the row of mesh wire cages. When detainees were punished with the “frequent flier program,” he’d moved men from one cell to another every two hours, round the clock.

“How can you wake up in Guantanamo and smile?” Holdbrooks asked them. “How can you believe there’s a God who cares about you?”

“I am happy to have spent time in Guantanamo,” said one detainee, the man who became his mentor, after his release. “Allah was testing my ‘deen’ (faith). When else would have I have five years away from all responsibilities, when the only thing I had was my Quran, and I could read it and learn Arabic and mental discipline?”

“Fortunately for us,” Holdbrooks said. “Most of them are bigger men than some of us would be.”

As Holdbrooks got to know the detainees, as he learned their stories during his long night shifts, he came to see the detainees as individuals. Many were men who enjoyed talking about the same things he does: Ethics, philosophy, history, religion. Many let him know what they thought of the 9/11 attacks: That they violate the teachings of Islam.

“Here, I had all the freedom in the world, and I’m miserable,” Holdbrooks said. “They have nothing, and they’re happy – it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out something’s going on.”

Tough kid

Terry Holdbrooks Jr. grew up a troubled kid with junkie parents who dumped him at 7 on his ex-hippy grandparents to be raised. By 18, he’d finished both high school – a year early – and trade school. He loved drugs, sex, rock-and-roll and tattoos – his ink would eventually cover his arms from shoulder to wrist. His earlobes have been stretched to a plug that a thumb could pass through.

So when Holdbrooks walked into an Army recruiter’s office in Arizona a year after 9/11 saying he wanted to join the Army, go kill people and get paid for it, the recruiter looked up briefly and turned back to his computer. “No, thank you,” the recruiter said.

“This was still right after 9/11,” Holdbrooks said. “The Army was flush with recruits, and they could take the cream of the crop.”

It wasn’t until his fourth visit to the office -- when he took the ASFAB, the military’s aptitude test -- that the recruiter realized Holdbrooks was worth pursuing.

Holdbrooks

signed up for military police because it offered a bonus. When his unit

was transferred to Guantanamo, the sergeant detoured through New York

to take them to Ground Zero.

Holdbrooks

signed up for military police because it offered a bonus. When his unit

was transferred to Guantanamo, the sergeant detoured through New York

to take them to Ground Zero.“Remember what Muslims did to us,” the sergeant told the soldiers. “Remember who you’re protecting.”

So Holdbrooks arrived at the hot, seared base expecting hulking killers in every cell. What he found were doctors, taxi drivers, professors. One scary “terrorist” was 12. Another was in his 70s and dying of tuberculosis. Holdbrooks identifies himself as antagonistic, questioning, independent person. He is naturally suspicious – and found his suspicions turning in a surprising direction.

“You start thinking, ‘Was I lied to?’” Holdbrooks said.

Priceless gift

In the time he had off from his escort and cleaning duties at the prison, Holdbrooks began reading more about Islam online. The prisoner he talked the most to, a former chef from England, gave him his own copy of the Quran.

“You’ve got to realize the significance of that,” Holdbrooks said, his tough bravado breaking for a moment. “He’s in this cage for 23 and a-half hours every day. If you lose your Quran, you’re out of luck. That’s it. You’ve lost everything.”

It took Holdbrooks three nights to read it. As a restless seeker in his teens, he had studied Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism, and never saw much sense in them. In the Quran, for the first time, he found a religious text that meets his logical criteria.

“It made sense from beginning to end,” Holdbrooks said. “It doesn’t contradict itself. There’s no magic. It’s just a simple instruction manual for living.”

After three months of intense study and conversation, one night Holdbrooks told the detainee that he wanted to become Muslim.

“No,” the man said.

“Whoa,” Holdbrooks said, stirring laughter during his talk in Huntsville. “The guard wants to embrace Islam, and the bad guy says ‘no’? I must really suck.”

The detainee explained what he meant. Converting to Islam meant Holdbrooks would have to change his life. Change his diet. Quit drugs. Quit drinking. Stop profanity. Quit getting tattoos. And be prepared for his relationships to everything – wife, Army, government – to change.

Little by little, Holdbrooks made the changes. Holdbrooks found a measure of health, discipline and peace of mind he’d never had before. And he found a family.

“Every little step I took toward Islam, Islam was taking more steps toward me,” Holdbrooks said.

One night in December 2003, he was ready to stumble through the declaration of faith in Arabic. He read from a card on which the detainee had transliterated into English syllables the Arabic words for, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God.”

“I knew I’d finally said it right when their faces lit up,” Holdbrooks said.

After Gitmo

But after Gitmo, when he rotated back to the States, he lost his grip on both peace and discipline.

■ Holdbrooks addresses an audience in the fellowship hall of the Huntsville Islamic Center in Huntsville, Alabama, May 25, 2013

■ Holdbrooks addresses an audience in the fellowship hall of the Huntsville Islamic Center in Huntsville, Alabama, May 25, 2013He was honorably discharged early -- for “generalized personality disorder,” the Army told him, although Holdbrooks wonders if his new faith influenced the decision. He and his wife divorced. He began trying to drink away his memories of Guantanamo.

“But you can’t drink away things like that,” Holdbrooks said.

By the end of 2008, he found himself wondering, “When was I happy?” The answer, he realized, surprised him: When he was in Guantanamo – because there he was being a good Muslim.

Holdbrooks been clean since 2009 – a victory he credits to following Muslim dietary codes, including daytime fasting several days a week all year, not just during Ramadan. Last fall, he married a nurse he met at his mosque. They had spent a year of careful getting acquainted in accordance with Muslim guidelines – which meant a lot of chaperoned visits. He’s finished a bachelor’s degree in sociology. He spends most weekends traveling with the Muslim Legal Fund of America to tell his story and to encourage Muslims to become involved in pushing for policy changes.

Holdbrooks is part of a small, but growing, number of former Gitmo guards who are speaking out about conditions at the center. But in addition for adding to the chorus calling for the camp’s closure, he has a message for fellow Muslims.

If the Prophet Muhammad were to come back to Earth today, Holdbrooks said, he would find the best examples of Islam in the United States. American Muslims have a responsibility to live their faith so others can see a true example, not the perversions of the terrorists or the tyranny of corrupt governments.

“You can’t be afraid to be a Muslim in public,” Holdbrooks said. “Tell your neighbors you’re Muslim. Invite them into your home. Invite them to visit the masjid to see our secret bomb factories.”

“If it’s time to pray – pray. The whole world is an acceptable place to pray.”

No comments:

Post a Comment